Jewish Germans Toni and Charlotte, among the first trans femmes to get gender-affirming surgery, fell in love and escaped the Nazis, before being arrested at the height of the war. This article was produced as official content for the first ever Trans+ History Week, one of QueerAF's launchpad projects.

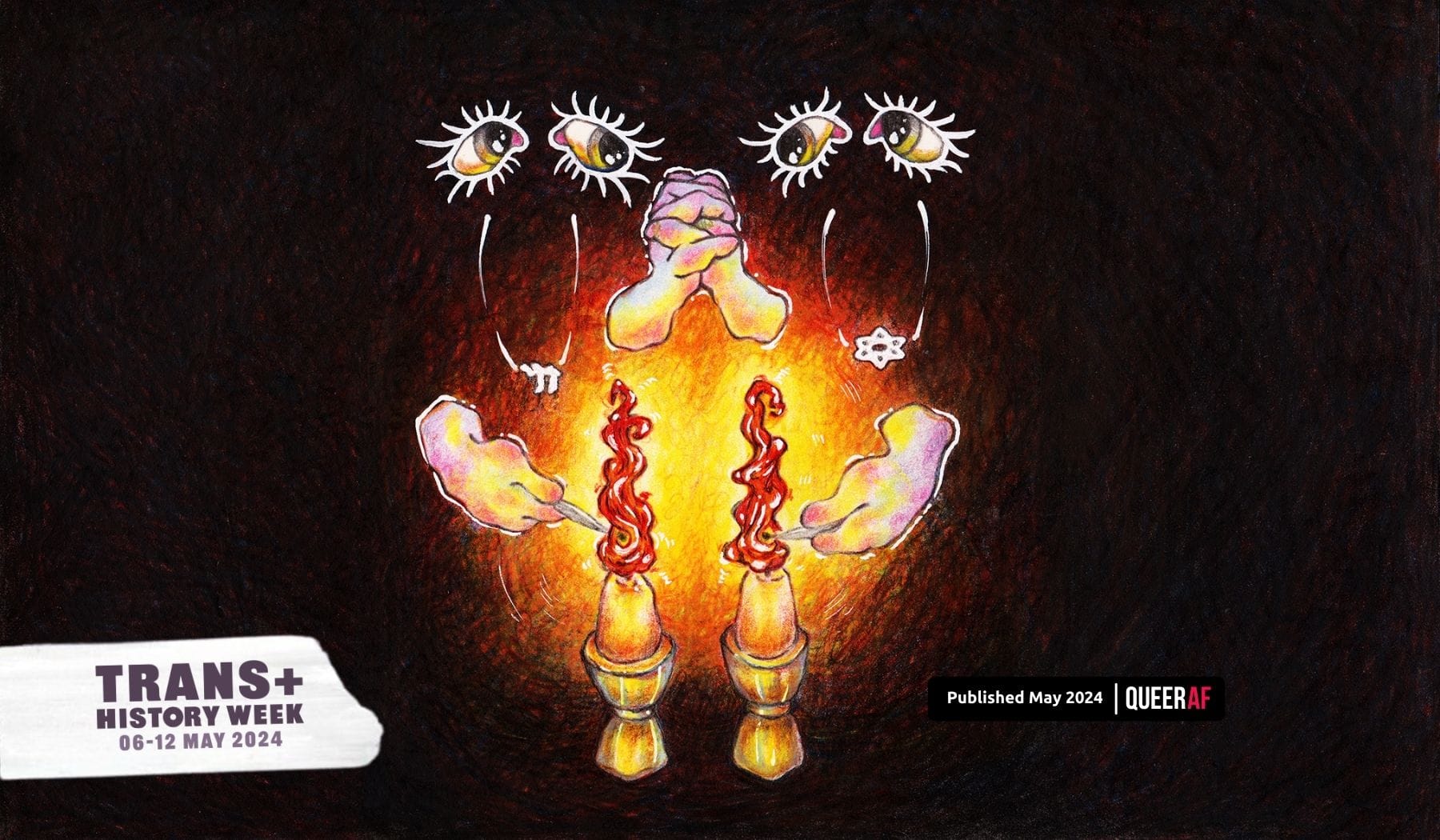

Prague, 1942. A refugee Jewish couple light Shabbat candles as night falls. The words of their Shabbes prayer ignite the Friday night darkness, alongside the hesitantly kindling flame. Together they create a holy space of rest in the middle of an increasingly hostile world that persecutes them: for their faith, their sexuality, and because both women are trans.

That was the reality of Toni Ebel (1881-1961) and Charlotte Charlaque (1892-1963) following their flight from Nazi Germany. But their relationship started years earlier.

Telling their individual story is, to me, a way to reclaim our communal humanity in portrayals of the Holocaust, which often condense us down to an undifferentiated mass of people.

As a trans and Jewish historian, when I watched Eldorado: Everything the Nazis Hate, which introduced me to Toni and Charlotte’s stories, I thought I was intimately familiar with the impact the rise of Hitler had on my communities.

I had worked hard for that knowledge.

My university Holocaust Studies classes and my non-queer Jewish community spaces didn’t discuss the persecution of LGBTQIA+ people during the Holocaust.

Queer Jews did – we teach each other our suppressed history. We talk about Magnus Hirschfeld and the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, a sanctuary for many trans and queer people, including Toni and Charlotte.

We are often the voices that tell others, LGBTQIA+ people and Jews alike, that the manuscripts being destroyed in the famed image of the Nazi book burning contained research on trans healthcare.

We speak out when anti-trans campaigners repeat Nazi propaganda about Jews funding transition care - propaganda that was used to destroy Hirschfeld’s Institut.

I thought I knew the stories.

But seeing actors representing Toni and Charlotte - trans, queer Jews - welcoming Shabbat just likeI do every Friday night moved me to tears I thought my years of research had made me too jaded for. It was a hand reaching out to me from the past with a message: “We have always been here. You are part of an unbroken lineage.”

Seeing the intimate portrait of survival, endurance and love between these two women showed me a through line of trans life from their generation to ours.

Toni and Charlotte met in 1928, in Weimar Germany (1918-1933), a time we often imagine as a haven for trans and queer people compared to the horrors that followed.

However, there was significant state interference in trans people’s ability to transition during these years - even in apparently radical cities like Berlin, with its bright, brilliant queer social scene, trans press, and trans healthcare centre - Trans Liminality and the Nazi State

Hirschfeld’s Institut facilitated trans people publicly wearing gender-affirming clothes, but only if the trans person carried a “transvestite certificate”.

This police-issued certificate told police that your clothes were a prescribed medical treatment for mental illness, and you shouldn’t be arrested for wearing them. Applying for one required a doctor’s letter - Deutsches Historisches Museum

Trans people also couldn’t legally change their name after transition without submitting evidence about their transness alongside letters from doctors. Much of Toni’s pre-transition history is known from her name change petition.

From 1920 onwards, if approved, a trans person had to choose a name from a Ministry of Justice sanctioned list of gender-neutral names like Theo, Alex, Toni or Gerd - Trans Liminality and the Nazi State

Because of this policy, we only know Toni Ebel by that name, and not ‘Annie’, the name she first applied to use upon transition. At the time, these trans-affirming practices were pretty radical. But they were ultimately still a form of state control on trans life - one we have not moved far beyond today.

How did Toni and Charlotte fall in love?

Toni and Charlotte were both Berlin-born Germans.

Toni left home over her family’s reaction to her transness. She explored Europe, becoming a painter, before returning to Germany and marrying a woman in 1908.

She developed PTSD after being conscripted during WWI, and became a socialist activist post-war.

Charlotte’s Jewish family emigrated to San Francisco during her childhood, and she returned to Germany in 1922, where she worked as a singer, actress and language tutor before settling at Hirschfeld’s Institut as a receptionist while undergoing gender reassignment surgery - Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft, Charlotte Charlaque

Then, as now, trans people often struggled to find work and housing, so a number of Hirschfeld’s patients worked or lived at the Institut.

One of Charlotte’s roles was to advise other trans femmes on clothing. During this work, Charlotte met Toni, who, now widowed, finally felt able to transition. Charlotte introduced her to Dr Hirschfeld, and Toni became a maid at the Institut while medically transitioning.

Toni and Charlotte, alongside Institut staff member Dora Richter, are the first known patients to have trans-femme bottom surgeries - Reflections on the Christine Jorgensen case by Carlotta, Baronin von Curtius (Charlotte Charlaque)

By 1932, Toni and Charlotte were living together and in love, calling each other ‘dearest’ in their letters. They appear together in the 1933 film Mysteries of Gender. Despite the increasingly hostile political climate, they look happy, beaming for the camera in fur-trimmed coats - To Be Seen: Wissen Diagnose Kontrolle

While living with her Jewish girlfriend, Toni chose to convert to Judaism, a choice we can assume was influenced by her relationship with Charlotte.

When I first learned this, it astounded me. Within interfaith couples, conversion often happens, but doing so during the Nazi’s systematic persecution of Jews is, to me, a profound expression of loving devotion.

It reminds me of the biblical Book of Ruth, which many queer Jews read as a lesbian love story. Like Toni, Ruth tells her Jewish beloved, “Do not urge me to leave you [...] your people shall be my people, and your God my God.”

🎨 Artwork description, by Nikolas Wereszczyński

"Toni Ebel and Charlotte Charlaque, the centre of the written piece, are also the focus of the illustration. I wanted to capture the warmth and the light of hope in the midst of darkness in early Nazi Germany, attainable for these women through both the Jewish faith (as represented by the Shabbat candles) and their own relationship where they are both equals, looking to each other, holding each other, and together kindling the fire. Overall, I decided to follow a more symbolic representation to reflect and sum up the article's themes of darkness, hope and authenticity while also using colouring pencils as a medium in a way that would create visible texture and give an impression of being much more tactile, alive, and down-to-earth."

In love, and fleeing Germany in 1934

Due to their identities and anti-Nazi politics, Toni and Charlotte were increasingly harassed by neighbours and police.

In May 1934, Toni says their Jewish community helped them flee to Czechia (Czechoslovakia). Following the German invasion of Czechia, on 19th March 1942, which was also their 10th anniversary, Charlotte was arrested while the couple were living in Prague.

As a Jew, Charlotte was marked for deportation to Theresienstadt, a transit camp on route to extermination camps.

Toni’s quick thinking, convincing the authorities Charlotte was American and that the US Embassy had her documents, spared her from the camps. Charlotte did not have papers because the US government refused to issue her a new passport in her chosen name.

As an American, Charlotte was deported to the US. Tragically, while Charlotte intended for Toni to join her, she was denied permission to leave Prague.

"I was now alone and initially had to suffer a lot, after 10 years of sharing joys and sorrows with a good person" - Toni Ebel - Perspektiven

Toni and Charlotte never met again, though they remained in touch for the remainder of their lives.

Post-war, Toni returned to East Berlin and became nationally famous as a painter. In contrast to her pre-war life, it appears she lived in stealth until her 1961 death. Little of her pre-war work survives.

She explains, in post-war testimony about her experience of fascist persecution, that much of her work was owned by Institut doctors as payment for transition care, and lost in the burning of the clinic. Last year, her surviving works were exhibited in Berlin - Toni Ebel - Perspektiven

Charlotte was a refugee in New York, and struggled to live between cultures. She wrote to Toni, "I, dearest, have no one with whom I could exchange a word or talk about things that are close to my heart."

She worked as a translator, actress and writer. By her death in February 1963, she was beloved by the local community. Her obituary was front page news, under the headline “The World Wasn’t A Stage, It Was Her Audience.” Her Brooklyn home is a New York LGBT monument - NYC Historic Sites Project

What can we learn from this history?

Toni and Charlotte lived defiantly, unrepentantly, in a world that said the penalty for doing so was ostracization and death.

Witnessing their story gives me strength. That is why I am so passionate about Trans+ History Week.

When we can see ourselves in the reflections of the past, we can find threads to draw strength from as we move forward in our own struggles, no matter how similar or different those might be.