Heartstopper star Kit Connor felt compelled to come out as bisexual on Twitter earlier this week, citing pressures from fans making him feel forced to come out when he wasn't ready to.

In the LGBTQIA+ community's push for greater media representation, biphobia and a sense of entitlement to other people’s personal lives is showing.

Why did this happen, and what can we learn from this? Here are three reasons and three lessons.

3 reasons why Kit Connor was 'forced' to come out

1. This debacle arose from misguided intentions.

The push for more representation of queer people across all industries is exciting for us.

We grew up in times when there was no positive representation of LGBTQIA+ people on the big screen, and so now, rightfully, we're demanding it.

The queer characters we’ve seen on screen have also often been played by straight actors.

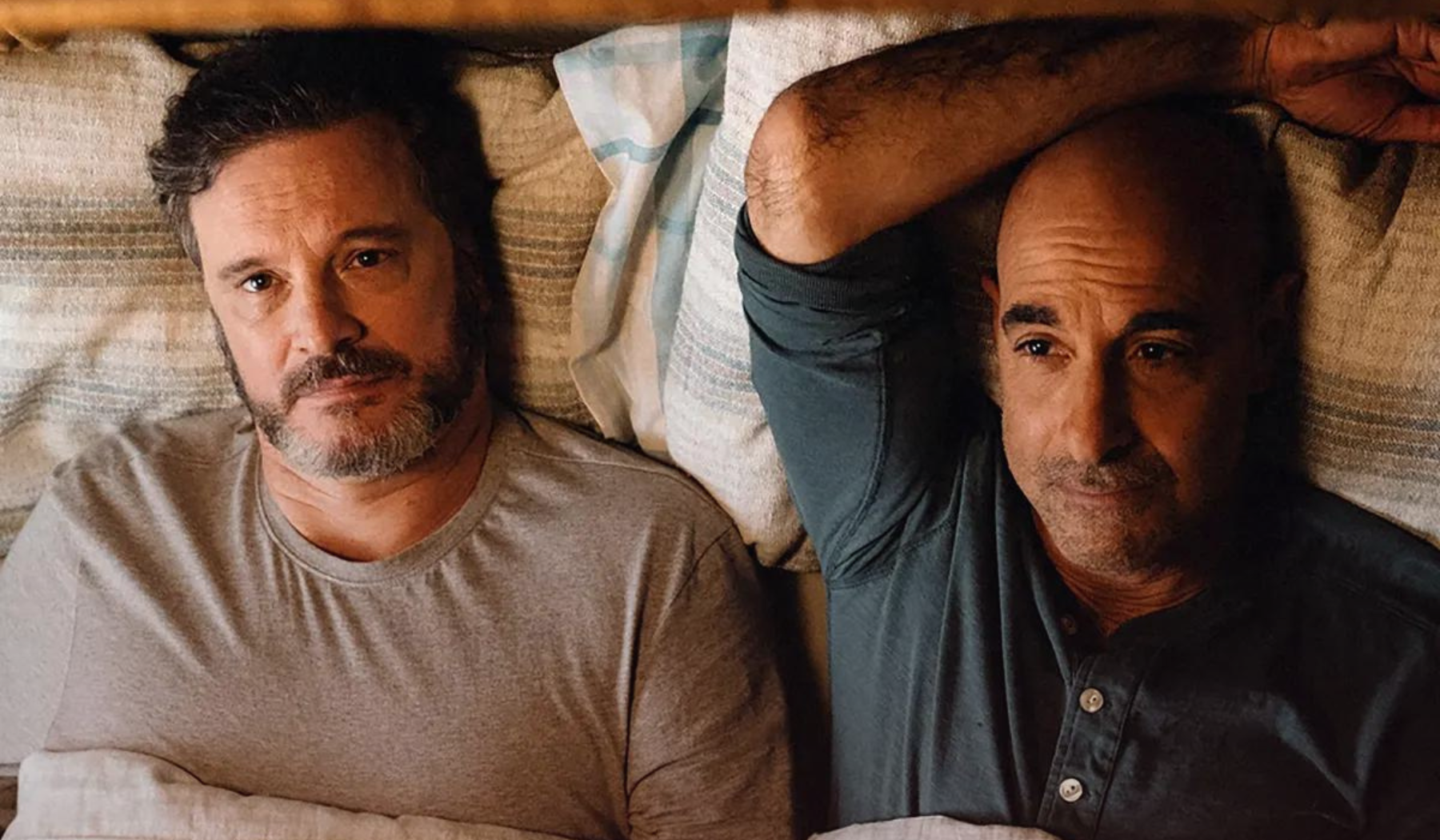

Colin Firth and Stanley Tucci acted in one of my favourite LGBTQIA+ films, Supernova (2020), but were heavily criticised as straight actors playing gay characters, yet again.

I had mixed reactions to those criticisms, as I found both actors to be excellent and compelling. Yet, I understand that there have probably been numerous LGBTQIA+ actors who have been cast aside for their identity. Some who could also have excelled in these roles.

All too often, LGBTQIA+ actors have been shunned aside or made to stay in the closet.

For Heartstopper, accusations of queerbaiting of a similar nature were thrown at actors who hadn’t publicly come out, such as Kit Connor.

People expected the titular character also to be LGBTQIA+ in real life.

I get it, people want more LGBTQIA+ representation. Though this is a good intention, this can result in pressure on individuals to come out, manifesting in a very entitled and toxic manner.

2. People feel entitled to other people's personal lives.

People seem to expect public figures to have little to no privacy. Some might say it comes with the territory of being a public figure, but at the same time, that reveals an entitlement that certain people 'owe' their privacy to you.

Just because someone is a public figure doesn't mean that they lose their right to their privacy.

Fans often feel entitled to information about celebrities’ personal lives. They might dig into the past, look into song lyrics, or analyse paparazzi photos, to try to figure out whether a celebrity is queer.

No one should feel pressured or forced to out themselves, which is what happened to Kit Connor.

The show Heartstopper was about having the space to explore and learn who you are without necessarily having to label yourself or put yourself in boxes.

People should not feel pressured to label themselves for others’ sake. Note that Kit is also very young, at just eighteen.

Perhaps some of us have figured out our identities from a young age (I knew that I was gay by the time I was in primary school), but many also take years to figure out who they are and come out later in life.

Even so, our identities can be fluid as we explore different expressions of our gender and sexuality and also be curious about the types of relationships we’d like to have.

3. Bisexuality is misunderstood. Biphobia is still common. Yes, even within the queer community.

Many people seem to misunderstand bisexuality, resulting in micro-aggressions.

Our community often upholds certain stereotypes about bi people, perhaps assuming they are going through a “phase”, or might favour straight-passing relationships over queer relationships.

I’m the founder of the LGBTQIA+ mental well-being app Voda. My teammate Claire (who identifies as bi) mentioned that once, in the queue for a popular queer venue in London, the person in front of her said:

“I love this venue because it’s for real people, not bisexuals. It feels genuinely queer.”

Many bisexual women like Claire say they feel excluded from their community. It is disheartening that many people say they wouldn’t date a bisexual person because of their proximity to men. Some are called “tourists”, and others face pressure to explain their dating history to prove that they’re queer.

Gay men also often assume bisexual men are "gays who are just not ready to come out yet".

I can speak from my personal experience where that myth comes from. When I first came out to a small group of friends like Kit, I was also eighteen.

I came out as bisexual. But I'm not bisexual. At the time, though, I found that identifying as bisexual might somehow ‘soften the blow’, both to others and, crucially - to myself.

But actually, I had just not yet dealt with my own internalised gay shame.

Many gay men with similar experiences assume bisexual men are just gay men with one foot out of the closet. But the thing is, everyone defines their queerness differently. Often, we project from our experiences, and these projections can manifest as biphobia.

3 lessons every LGBTQIA+ person should learn after queerbaiting 'forced' Kit Connor to come out

1. Continue to push for greater LGBTQIA+ representation.

We can push for greater media representation for LGBTQIA+ TV shows and movies to be made and for LGBTQIA+ actors to be cast in those roles.

We can celebrate greater LGBTQIA+ representation on the big screen, like the Bros movie, which was one of the first gay romantic comedies featuring an openly LGBTQIA+ cast.

Unfortunately, it flopped at the box office despite being enjoyed by many. So perhaps our energy can be galvanised towards supporting LGBTQIA+ movies and media rather than attacking or policing one another.

2. Criticise institutions instead of individuals.

The furore over “queerbaiting” has caused quite an uproar recently. So can queerbaiting exist? I still believe so.

Most commonly, it exists when brands or companies try to market themselves as LGBTQIA+ friendly when they are not. Do they have a rainbow logo up during Pride but perhaps have trans-exclusionary policies? That’s not cool. That’s queerbaiting.

What about companies like Grindr? Until recently, Grindr didn’t even appear to be queer-led, and the company has had numerous privacy violations. It might have even sold off sensitive user information of its queer users.

The LGBTQIA+ community continuing to hold Grindr accountable seemed to have fostered certain strategic changes, too, such as recently appointing a majority LGBTQIA+ board.

This beckons good news for the queer community, and perhaps we can now have greater faith that the company would have our wider community's interests at heart and are not simply just in it for the money.

I’d even lob an accusation of queerbaiting towards the current UK government.

The state might pay lip service and proclaim that they are queer-inclusive. Still, their actions beget otherwise with their exclusion of trans people from the conversion therapy ban and their queer-exclusionary rhetoric.

Accusations of queerbaiting can be harmful and detrimental to our overall cause.

Specifically, the discourse around queerbaiting can be harmful when directed towards individuals instead of organisations because it underpins a flawed notion that people are entitled to information about other people’s sexuality or gender identity.

3. Stop pressuring people to come out and accept them as they are.

We can also push for this greater representation without pressuring people to come out.

You might believe your curiosity to be innocuous, but repeated pressures and intrusive questions when someone has expressed discomfort is toxic behaviour.

No one is obliged to answer to someone else on their sexuality or gender, and whether we decide to disclose our queer identity (or not) is our prerogative.

We don’t have to understand someone's lived experience to accept them.

We often project from our limited lived experiences. As a cis gay man, I will never truly know what it means to be trans, or to be a woman, or to be straight or bisexual. But I don't have to understand someone to respect their lived existence.

This is, after all, is what our community has been fighting for this whole time in a heteronormative and cisnormative world: for our loved ones to accept us, just as we are, unconditionally.